My Experience with Half-Life

This past winter, I took advantage of Steam’s holiday sale and searched for something fun and cheap. I came across Half-Life, a first-person shooter from Valve, the company behind Steam. I didn’t really know a whole lot about the game other than it being held in high regard. I bought the game because it was the reviews and trailer painted a good impression, it was only $2.30 CAD plus tax, and it would easily run well on my potato of a laptop. But I didn’t jump into it immediately…

Half-Life gained plenty of dust on my digital shelf for months as I was occupied with my re-run of the entire Uncharted series and going through campaigns in Balatro and NR2003. Starting work in January made free time less dispensable. In August, I searched for a new experience, preferably a campaign to try out. I looked at my inventory for something fresh and unique… and Half-Life fit the bill. And here starts my journey into Black Mesa.

As of writing, I have logged 7.6 hours of gameplay and have progressed to the “Power Up” chapter. Per online estimates, this places me close to the halfway mark of the campaign. It was quite an experience to play a game that was published before I was born: There were fewer autosave points than in newer games (which meant plenty of manual saving!) and while the low-res textures and blocky geometry were charming in their own way, they really do date the game.

But the main thing about Half-Life I could not ignore upon realization is how much it shows and how little it tells.

In some of the other games I played like Uncharted or Zelda, the narrative and the environment can be explained directly to me or through clues left in the environment to infer from. With the games I mentioned earlier, they tell the narrative based on character dialogue, cinematic cutscenes, and environmental cues to direct the player. For example, a ledge with grooves suggests I should climb it, or there are markers and waypoints jotted on a map to follow.

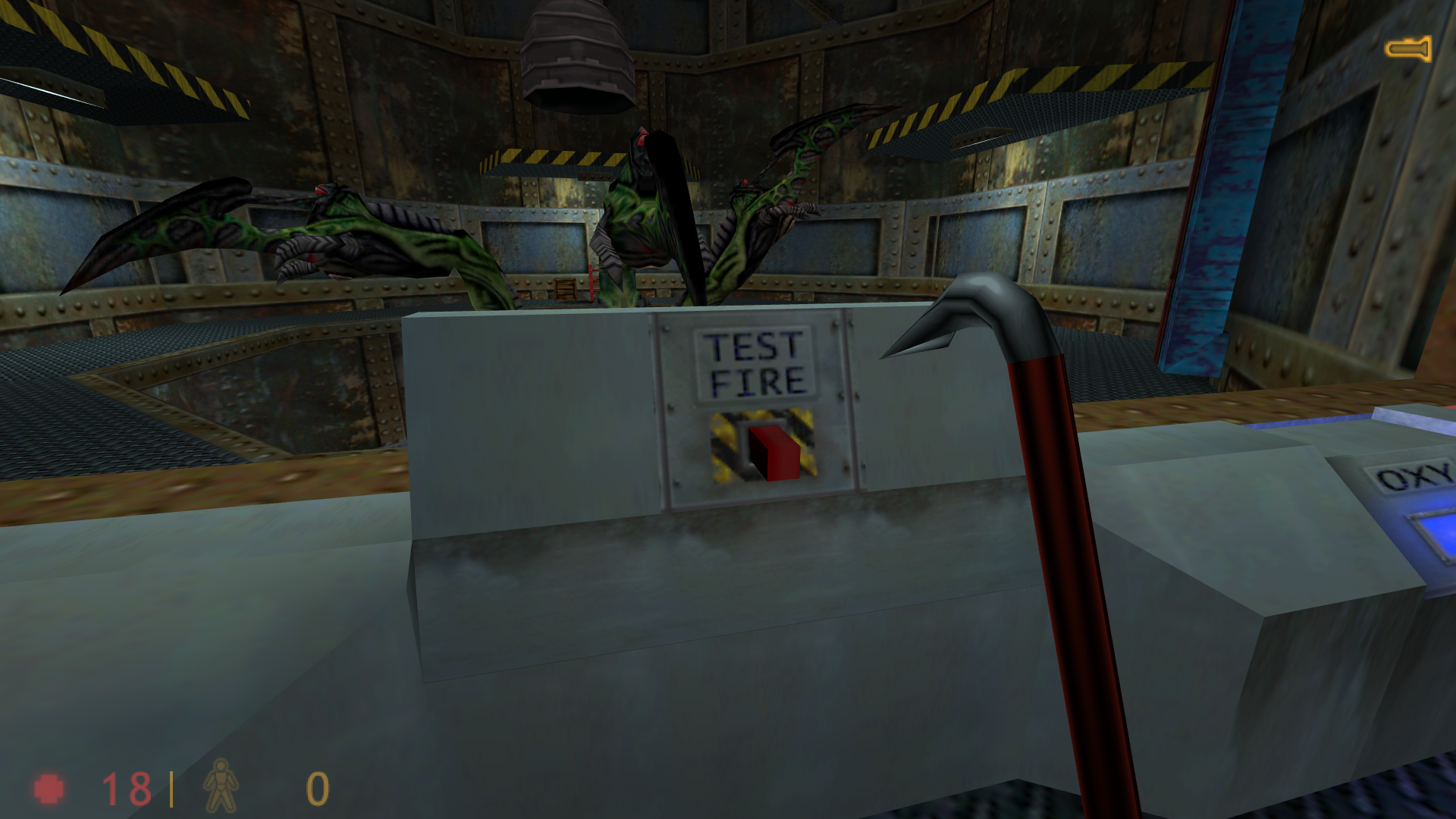

Half-Life leans way, way into the latter method. I was not given a heads up on… anything, for the most part. To get just a gist as to what Gordon Freeman does in Black Mesa, I had to meet a few scientists and listen to their small talk. After a scientific experiment went awry and sent the entire complex into chaos, I was thrown into the frying pan alone. There was no map to guide me. Instead, I had to look at the world around me for clues. There was no warning about the monsters I encountered and had to kill for my survival. And my expectations were flipped on its head when the US military came in to destroy the base and its occupants (including me). I only figured their motives out when encountering a scientist hiding for his life.

Half-Life is a game that leaves everything up to the player. It’s designed to challenge me to figure out crap as I go.

“Oh, this button isn’t launching the rocket that will blast the giant eldritch monster away? Gee, tough luck. Guess you’re stuck in the chamber with boarded-up doors and a box of grenades with a blind monster that is sensitive to noise”

It stands in contrast to my gaming experience where I had waypoints, more frequent dialog, adventure logs, copendiums, and so on. I don’t think one is better than the other. Any position taken on the show/tell axis can work if executed properly. In a way Half-Life reminds me of another game that leaves you to your devices: Inside.

Inside is a small indie horror game published in 2016. The game uses no dialogue and does not explain what the hell was going on. Instead, it simply showed you the situation and used the environment to implicitly instruct you. The narrative is never exposed directly, leaving me to make my own guesses as to what the story was all about. Its absence of explicit information is a degree higher than Half-Life, where there are bits of dialogue to get information from, but we are expected to find out how to progress on our own.

The big takeaway I got from this ramble is how powerful the “show, don’t tell” technique can be in game design. I cannot imagine this being an easy thing to pull off and certain contexts have their constraints. For example, I don’t think you can really leave the player aloof in a strategy game without giving them information on enemies or resources or whatever. Nor can you tell them literally everything if you want to maintain an element of surprise.

As for me… well, I’m gonna continue my journey to figure out what other stuff is getting thrown my way. I may make a follow-up to this post when I finish the campaign, and that would be it.

After all, it’s a Valve game… you can’t really expect things to come in threes…